Writing Memorable Settings: Turning Space into Place, Act 1

Take a look at the room you’re in.

If I asked you to write a story set there, which details would you use?

The color of the walls? The way the light comes in through the windows? Maybe something about the chairs. With those details you could sketch out a pretty good picture of the room. Your reader would be able to see it. But would the setting add a feeling or emotion to your story?

As writers, we describe our settings, but we often stop there. We treat our setting like a backdrop. A few details – the color of the fabric on the chairs. The puddle of slush by the door. We might allude to a feeling – the moody room or haunted house – but setting can be so much more.

By the end of this series, I believe you’ll appreciate the full potential of setting to raise emotional stakes and reinforce your themes and – perhaps most importantly – to make your reader connect with your story. And that connection is, ultimately why we write.

My overall interest is to share some insights about the psychology of place so we can apply this knowledge to our writing. At the end, you’ll have some key questions you can use to create emotionally resonant settings. And of course, it seemed appropriate to tell this story in three acts.

In act one we’ll learn about place attachment – the emotional heart of setting – in act two we’ll examine how Cynthia Voigt used place attachment in two of her novels – and in act three we’ll explore key questions you can use for your own work.

The resources and prompts we’re going to use are in the worksheets.

Both acts one and three have some prompts, so – pencils out – let’s begin with a place you know well. Choose a place that has meaning to you. A favorite location, a place you’ve visited a few times, a friend or family member’s home.

Got it?

Now, write how you felt about that place the first time you saw it and how you feel about it today.

Then I’d like you to move to the next two boxes and write down WHY you felt that way the first time, and today.

Give yourself two minutes.

| First time I saw [my place]: | [my place] today: |

Okay – how was that? Were you able to easily name your feelings about the place you selected?

Did you notice changes between the first time you saw the place you selected and today?

Were you also able to identify the “why” behind the feelings?

That may have taken a little extra thought because we usually stop after we identify the feeling itself.

This is College Hall, home of VCFA in Montpelier, Vermont.

The first time I saw College Hall in person was a snowy day in January of 2018. I flew up from North Carolina and a college friend of mine who lives in Vermont dropped me off outside in the snow.

I knew nobody here.

As my friend pulled away, I experienced a surge of homesickness. It was identical to how I’d felt years ago when I got out of a taxi in Washington DC and had to walk into my new dorm alone, dragging two heavy suitcases and scared that I wouldn’t know what to do, that I wouldn’t make friends, and that maybe this wasn’t such a great idea after all.

My first impression of College Hall was that it loomed over me. It was creaky. Unfamiliar. And intimidating. Could I live up to everything it stood for?

And that basement? More than a teeny bit scary.

It was like being 17 again, thinking what the heck am I doing here?

After two years, College Hall felt different. It was filled with friends. I learned so much in those rooms. (although the basement remained pretty creepy.)

When I see College Hall now, I feel lucky, accomplished, and surrounded by love. These bricks haven’t changed, but I have, and this place literally looks different to me.

You each have your own places and stories about those places – you have your own emotional associations with those places, just like other people have their associations with College Hall.

Here’s how I know that’s true: Instagram.

Space becomes place when we endow it with meaning, and for everyone who took these photos, College Hall has some kind of meaning. It’s a symbol of learning, change, aspiration, friendship, and transformation …. or looming packet deadlines. That’s why it’s all over Instagram. It means something to us. It’s not just a pile of sticks and bricks, it’s a symbol. It embodies our feelings.

Space becomes Place when we endow it with meaning.

As writers, we need a language to talk about these emotional aspects of setting because it’s the secret sauce that makes your reader connect with setting the way I connect with College Hall.

This is so obvious that it’s easy to overlook, but there are actually people out there in the world studying why we have these feelings. Their research tells a basic truth: humans are wired for place, just as we’re wired for stories and emotions.

There is a language for this connection – it’s called place attachment – and I learned about it the first time I went to graduate school for my Master in Urban Planning degree.

Since then, I’ve spent the last 25 years literally working on place. I’ve worked in New Jersey, New York, California, and North Carolina. These are photos from my work in Chapel Hill. My day job has profoundly affected the way I think about setting.

I’ve spent years learning what makes somebody want to walk around downtown and maybe sit at outdoor table. I’ve worked on projects to turn unused alleys into landmarks people actually want to take a selfie in front of. I’ve studied how landscape and setting change our behavior. But it wasn’t until I came here that I connected that part of my life with my writing life.

The study of how we interact with place comes out of Environmental Psychology.

This research offers a vocabulary and a framework we can use. Once we know how to think about place, we can understand it, probe it, ask better questions, and write better settings.

The good news is you don’t have to be an urban planner to speak this language; you just have to be human.

So – what is place attachment?

We feel safe in certain physical environments.

Unsafe in others.

Architects and landscape designers understand these emotional reactions to space when they design.

So do decorators.

So too, should writers.

Our relationship to our setting is an essential part of being human.

As I began thinking about how my two worlds of planner and writer connected, I got curious about setting in the craft of literature. So I did what most writers would do….

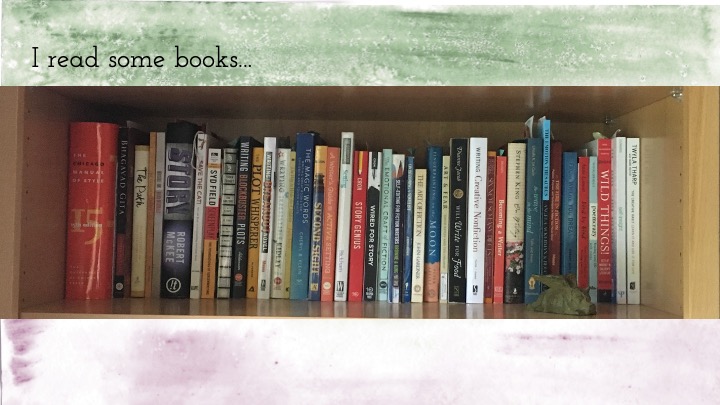

I surveyed a variety of craft books, from general writing advice to ones devoted entirely to setting, and most of them said something like this:

Other common advice was to include a few well-chosen details and focus only on what your point of view character would notice.

I think in our current culture, with its emphasis on film and television, some of the writing advice we get reinforces the idea of setting as backdrop.

We’re very visual animals, so most writers will describe visuals first – this fits with the scriptwriter’s approach.

We think about the reader as a viewer of the story in their head, and we keep their lens focused on the characters and the action.

We study the brain science of reading. Electrodes show us that when you read “left hand” the part of your brain that connects to your left hand activates.

At some level, you “feel” what the character feels. This is part of why we clutch that crime novel, why our heart pounds when Stephen King terrifies us, and why we shed tears when a beloved character dies. Sensory details immerse the reader in the story. We feel it.

So the setting advice to “add specific details” is headed in the right direction.

As writers, we know our characters will notice details that fit their psychology and their situation. We push for authenticity, and our readers respond.

But place attachment goes beyond the details.

It’s based on feelings and memories, which are less easily measured with electrodes. It’s a complex mix of experience plus place plus associations plus personal perspective. And, it can change.

Let’s go back to the craft guidance.

Mary Kole is right, but in general, the craft advice doesn’t go deep enough if you want to know HOW to pack the thematic and emotional punch she’s referring to.

We know what doesn’t work when we write for children in our primarily western, modern audience.

Overly detailed descriptions, lingering on the lace curtains and doilies, the flowers on the tea kettle, and the exact slant of the light as it hits the horsehair sofa that our great-grandmother brought to California on a covered wagon gets in the way of what readers care about, which is the character and their needs and actions.

So how shouldwe handle setting?

This is where place attachment comes in.

We don’t just want our readers to see the setting.

We want them to relate to it – to feel it like they felt their left hand.

Consider how understanding setting as a backdrop is different from relating to setting.

In backdrop mode, our characters are not attached to space. It’s there. They see it, the reader sees it, but it’s not integral to our character’s mental state.

When a character relates to a setting, it is integral to their mental state because it has meaning.

Readers get this.

You get this.

All those instagram posts of College Hall….

As writers, we study the craft, we spend a lot of time polishing our skills. We observe carefully, we choose our words to carry emotion, information, and plot. We study our craft in order to connect with our readers through our character’s motivations, their struggles, and their achievements.

Yet we spend relatively less energy on settings.

I think most of us get this, but we’re doing it on instinct. Having a language matters.

When I was a kid all the trees were the same species: Green.

As I learned different tree names, the green blobs started changing. I noticed bark patterns and leaf shapes. Trees became unique. When you have a language and a way to name something, you can begin to study it and understand it. This is true for trees and anything else you’re an expert in. You learn the language.

As writers, we need a language for place.

With a language we can understand the emotional resonance in settings. We can be deliberate about crafting our settings.

Let’s go back to the definition of place attachment: Space becomes place when we endow it with meaning.

How many of you had a favorite, safe place when you were a kid? Maybe your room? Or a fort or hiding place? Close your eyes and picture that place in your mind.

How do you feel?

Positive place bonds tend to support positive memories, a sense of belonging, and our idea of who we are. Perhaps you were calmed just now. Or nostalgic.

We feel comfortable in settings that remind us of our safe havens.

But place attachment is not always positive.

Close your eyes again and think of a place where you felt unsafe as a kid.

Try to really see it.

I’d bet you had a physiological reaction to that memory. Perhaps your heartbeat accelerated. Or you tensed up.

Places where we’ve experienced sadness or trauma can imprint as anxious or fearful templates.

We tend to avoid places that remind us of our wounds.

This effect been called the shadow side of place.

Sitting here today, you had a reaction to those two memories.

Attachment and Shadow.

Imagine your reader feeling that way when they read your words.

That’s emotional charge and that’s what we’re after.

Stories are about change and our place attachments change with time and attention.

We may grow up and leave.

We may try to recreate a special place from our childhood.

We may leave a negative place and seek one that better matches who we are.

Or we may choose to alter a place to meet our needs.

Decorating a college dorm, finding a new home, or redecorating after a divorce or family change – these are all ways of creating a new identity through space.

The new space is “the new you.”

People change.

Places change.

These are the ingredients that go into emotionally resonant settings.

Okay – to summarize Act One –

Place attachment is what happens when we attach meaning and emotion to a space.

That attachment could be positive or it could be negative – the shadow side.

Which brings us to act two.

This series is adapted from my critical thesis for an MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts.