Writing Memorable Settings: Turning Space into Place, Act 2: Homecoming

To explore these ideas of positive and negative place attachment, I chose to focus on middle grade settings, and home in particular. However, these concepts do apply across genres and across ages.

Why middle grade? Between our childhood and teenage years, we begin to see the world through new eyes. We observe carefully, we make judgments, and we decide how we feel about our surroundings. We consider how other people see us. At this age, we may want to change our space, almost like trying on new aspects of our evolving personality –yet the space is often controlled by adults in our lives who may limit or discourage the exploration.

Home is, of course, a special place. It is the archetype and a metaphor for our strongest emotional bonds. This is why realtors sell homes, not houses. We’re buying the story of who we are, not just a place to sleep.

Young readers get this. They’re creating the myths that will shape their lives. Their setting is tied to their story. They may hold onto their story of who they are for a long time.

It’s no wonder that so many stories focus on finding home or feeling displaced from home.

So, Let’s see how one masterful writer used place attachment to create some unforgettable books.

When I read Cynthia Voight’s Tillerman Cycle novels many years ago, I was changed. These books struck me to the core. They remained vivid in my memory for years. I felt these people, I traveled with them, I remembered these books.

Cynthia Voigt is a master of emotionally resonant settings and her work merits a close look.

The books are set in the Eastern Shore of Maryland, a place where Cynthia Voigt has strong personal connections.

In Homecoming, she showcases the “house as haven” concept of place. In A Solitary Blue, she explores the shadow side of place. They are excellent bookends for these two aspects of place attachment.

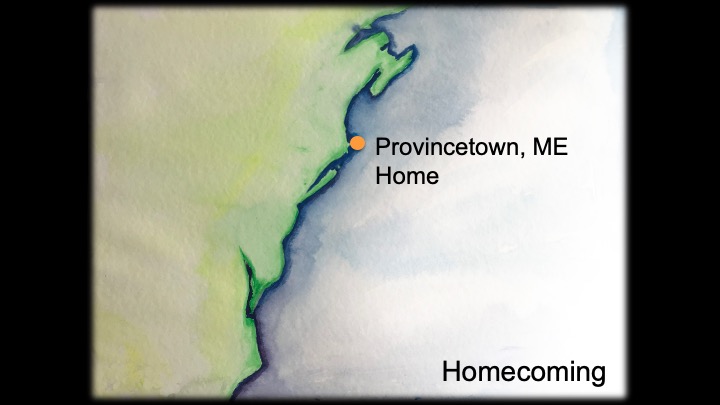

Dicey and her siblings – Sammy, Maybeth, and James – live with their mother in Provincetown, Maine.

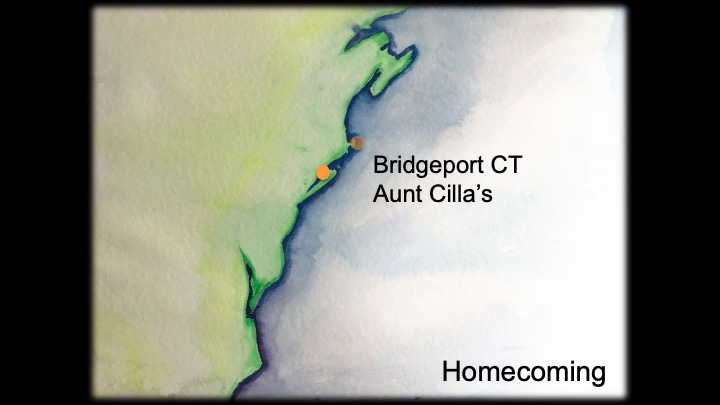

The story begins when they are abandoned by their mother in a shopping center parking lot, on their way to their Aunt Cilla’s house in Connecticut. They have never met Aunt Cilla, but when they realize their mother isn’t coming back, they decide to walk to her house.

Early in the story, we read “Home, for Dicey, was their house in Provincetown, where the wind made the boards creak in a way that was almost music.” (103) She also associates home with the ocean, her need to run and move freely, and Momma.

As they travel, Dicey’s definition of home changes.

Dicey imagined Aunt Cilla’s home in Bridgeport would be like the one she’s lost. This is what she needs – it would also connect her to her missing mother.

But once she’s inside Aunt Cilla’s house, Dicey feels trapped, closeted, and lonely. The house is narrow and dark. The rooms are small. Dicey only feels like herself when she takes her siblings to the ocean on the weekends, where they can run and shed the confines of Aunt Cilla’s expectations for proper behavior.

Dicey’s concept of home continues to evolve – “she no longer hoped for a home. Now she wanted only a place where the Tillermans could be themselves and do what was good for them.” (206)

In the middle of the book, when Dicey is trying to make the most of this new setting, she learns that she and her siblings may be separated. They’re the last part of home that Dicey clings to and losing them would mean losing “home”.

So Dicey decides to risk running away to their estranged Grandmother’s house.

Dicey is scaling down her definition of home, but the reader feels the tug of Dicey’s emotional truth. We know that home – the wind, the freedom, and her family – is essential to her. Cynthia Voigt has layered the story with meaningful place elements and shown us Dicey’s emotional associations to them.

We read on because we have to know: will Dicey find home?

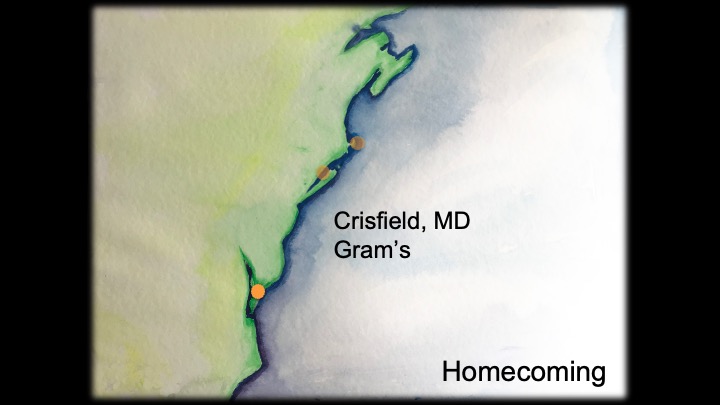

In the final quarter of the book, when the children make it to Crisfield, their grandmother rejects them.

She doesn’t want them and she doesn’t want any responsibilities. Gram’s home is hers alone now. Her overbearing husband is dead, her children are all gone. She is finally free and she refuses to relive the past and it’s negative associations.

Gram sees her home as a prison from which she’s finally escaped.

She’s not going to lock herself in with responsibilities.

The children try to stay, extending their visit by pulling weeds and vines, and clearing out the barn.

As they work, trying to prove their worth, they are gradually changing their grandmother’s setting.

They are also forming new attachments. Their grandmother’s house was their mother’s home and connects them to her. It smells like the ocean and the Provincetown house. Dicey’s room has a view to the water. There are books for James and plenty of room for Sammy. This place echoes and mirrors what they’ve lost.

It is new, but familiar.

It meets their emotional needs.

When their grandmother definitively says they must leave, we are crushed.

Why?

Because, as readers, we feel this – we know what it’s like to have a special place, and lose it.

We want the children to be welcomed and to stay because that’s what we want for ourselves. We don’t just look for a place to sleep, or a shelter. At heart, we all want to belong someplace that reflects who we are: we all want a home.

This is emotional resonance through setting.

At the very end of the book, Voigt brilliantly masters the dynamic emotional bond of place.

The children go to town with their grandmother to send Aunt Cilla a letter asking her to take them back. They stop in the grocery store where their grandmother introduces the children to the owner as “her grandchildren”.

Outside the store, she tells Sammy he can call her Gram.

Dicey decides to ask one last time if they can stay and Gram says, “I give up. You’ve worn me out. You can stay, you can live with me.” (387)

Why does she change her mind?

Because through their work, the children have altered her physical setting.

Before the children arrived, Gram was experiencing the shadow side of place. Her setting was filled with negative memories.

The children have literally changed her setting and they’ve created new associations with her. Gram cared for Maybeth’s arm when Maybeth was hurt. James has ideas for how to make the farm productive again. Sammy reminds her of her beloved son.

Gram can imagine a different future for herself.

So can the children.

Perhaps you can imagine a new future when you step into your favorite place.

Cynthia Voigt said of Homecoming, “The Tillerman story is pretty much an autobiographical geography of my youth. And my adulthood.”

The writer feels this place. She knows it by heart and experience, and she’s used specific details to make us see the setting, but she’s also connected those details to the characters’ transformations. The change in setting and the change in characters work hand in hand.

This is place attachment.

This series is adapted from my critical thesis for an MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts.